From Clubhouse to India's Parliament: the Unlikely Rise of Sikh Separatist Candidate Amritpal

Amritpal Singh is running for a Lok Sabha seat in India’s 2024 elections. What will it portend if he wins on June 4?

A massively important election—featuring a candidate running from jail.

The election in question is India’s national election for the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, that will determine the next government. The final stage of the weeks-long process consisting of seven stages occurred on Saturday.

The candidate who ran from jail is the leader of a movement—or an outlaw, depending on who you ask. He is Amritpal Singh, a Sikh preacher and radical separatist, who has been in police custody since April 2023. He is running to represent the northwestern constituency of Khadoor Sahib in Punjab state.

Whether he wins or loses on June 4, his candidacy has reverberated far beyond his district, and beyond India, into the Sikh diaspora around the world. For the latter, Amritpal has become a symbol of justice for Sikhs, and in an important sense, one of their own—having arisen from the social media circles where Sikh activists outside India commiserate. Within his constituency, his stature comes from being the current leader of the farmer justice group Waris Punjab De (WPD) which means “heirs of Punjab”. For India, Amritpal portends a return to the harrowing decade of the 1980s, when the Sikh insurgency in Punjab tore at the seams of the nation and caused the death of thousands.

On June 1, the 1.6 million voters of Khadoor Sahib, which borders Pakistan, chose between Amritpal and four other candidates. While Amritpal is ran as an independent, the four other candidates represented four major parties: the Indian National Congress (INC), the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP).

All four of these parties have a strong presence, either in the state of Punjab, or nationally, or both. The BJP, under Narendra Modi, has controlled the central government of India since 2014. If opinion polls are correct, Modi is likely to return to power. The AAP is the current ruling party in the state of Punjab. The INC is the grand old party of the Indian independence struggle, and the SAD is similarly the grand old party of Sikhs. Both have been in power in Punjab for years at a time.

According to exit polls, the results on June 4 look like they may favor Amritpal. “The wind is blowing Amritpal’s way,” a local publication said. That would be a remarkable feat. His rivals’ races have the heft of their parties behind them, while Amritpal is running as an independent without a party structure.

Amandeep Singh, independent researcher in California and board member at the California Sikh Youth Alliance (CSYA), who has known Amritpal for several years and supports his candidacy, chalked it up to the emotional connection Amritpal has built up with voters. “Folks like Akali Dal in this constituency have been dominant since 1947, and they’re going to suffer a huge defeat from a kid who’s not even 30 yet,” Singh said. Amritpal has gone beyond being a mere political phenomenon, Singh pointed out; he is often greeted by villagers with tears in their eyes.

However, Amritpal has not set foot in the state for more than a year. He is being detained under the much-derided colonial-era National Security Act that allows for preventative detention, without recourse to trial, anywhere in India. Amritpal is being held more than 1,500 miles away, in a maximum security jail in the eastern state of Assam. He has only been a candidate for a month, having filed his candidacy in early May, with his filing attested by jail officials.

But Amritpal is no ordinary prisoner.

Ever since his return to India in 2022 after ten years in Dubai, he has styled himself a preacher, and led a movement for a return to a traditional form of Sikhism among the youth, tinged with militancy and separatist politics. He has spoken in favor of gaining independence for Punjab from Indian occupation to form a separate nation for Sikhs, called Khalistan.

Indian Intelligence has alleged that during his stay in Dubai, he received military training from Pakistan’s intelligence agency ISI, though they have not provided evidence for this allegation, nor has it been charged.

Amritpal became involved in Sikh activism during the Punjab farmer protests of 2021. At the time, Punjabi actor Deep Sidhu had become the center of a virtual global mobilization of Sikh activists supporting the farmers, and seeing larger issues of justice in their struggle. Some of this virtual gathering took place on the now-defunct Clubhouse voice chat app. Amritpal was one among the group. He became well-known due to his forceful presentation of ideas.

Deep Sidhu founded the WPD group as a vessel for this activism. After Sidhu’s death in a mysterious car crash in February 2022, Amritpal was chosen to be the new leader.

Amandeep Singh of CSYA was in the Clubhouse conversations with Amritpal during the phase when he assumed a leadership role. “Amritpal grew up in these towns, these villages, where he saw this violence, felt it generationally,” Singh said. “He was a loud charismatic voice and he was able to digest these different critiques in his own vernacular.”

At this time Amritpal was still based in Dubai and planned to lead the group remotely.

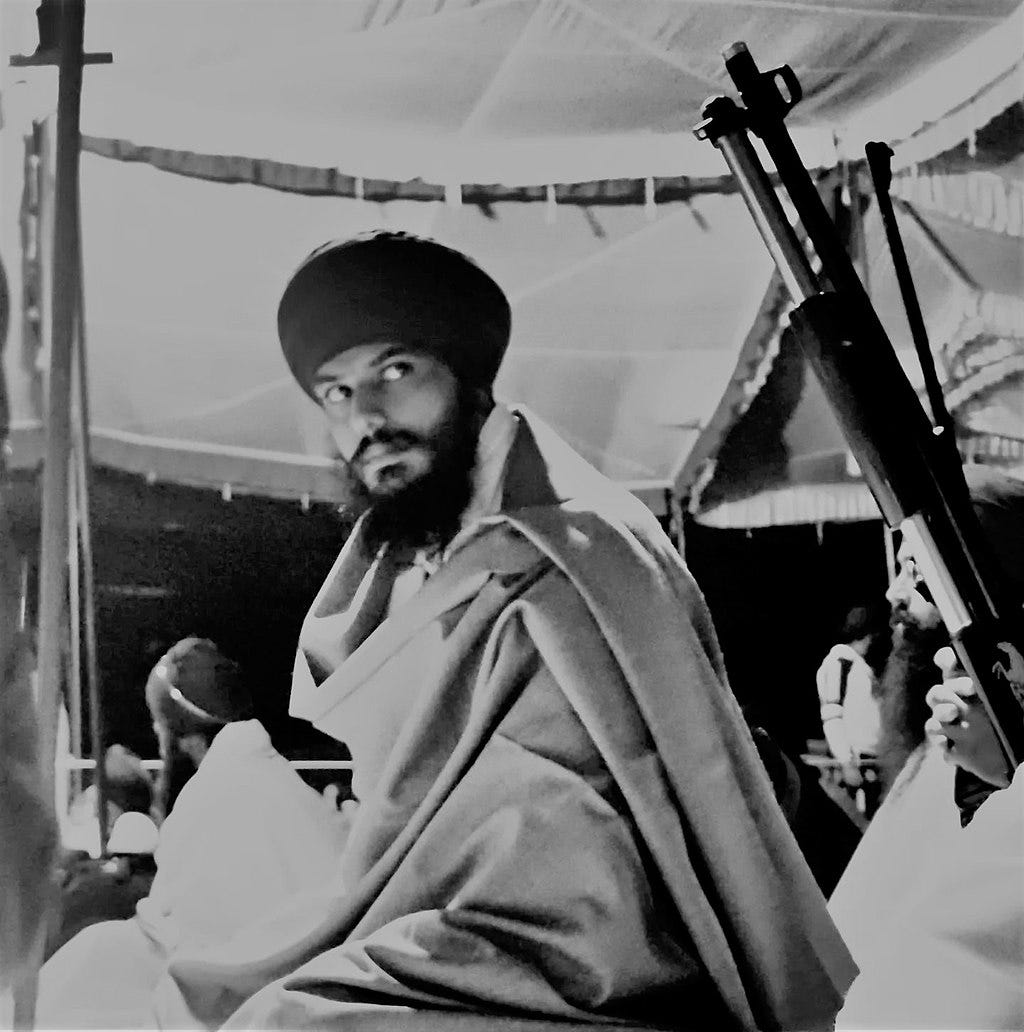

In August of that year, he returned to Punjab, hailed from abroad by Sikh temples as far flung as ones in Canada and New Zealand. In September, he was feted in the town of Rode in a turban-tying ceremony. It raised eyebrows, both due to his comments favoring secession, and the special significance of the town of Rode in the Indian consciousness: Rode is the birthplace of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, militant Sikh cleric, who led the insurgency in Punjab during the 1980s.

Bhindranwale was killed by the Indian army on June 6, 1984 during Operation Bluestar, a military operation to flush out Bhindranwale and his militia from the Golden Temple, a holy shrine of the Sikhs in Amritsar, where they had fortified themselves. In the forty years since, he has become a symbol of martyrdom for Sikhs. The banner for Referendum 2020, a project that is holding a nonbinding vote among Sikhs worldwide for secession from India, prominently features Bhindranwale’s piercing gaze.

During the turban-tying ceremony, Amritpal made comments about Sikhs being slaves in India, which is understood as being a call for secession. Khalistan slogans were raised by his supporters. He also dressed like Bhindranwale with a blue turban tied in the same way, and styled himself a preacher. This was very much a transformation from his prior look, clean-shaven or with a trimmed beard, and westernized clothing.

He was heralded as “Bhindranwale 2.0” in the media. For India and for Punjab, still haunted by the trauma of the insurgency of the 80s, there could not have been a more triggering moniker.

However, Amritpal began preaching a message of peace, and working to bring Sikh youth back into the fold of the religion. In particular, he spoke up against drug addiction among young men, which has been a major scourge in Punjab, ravaging families in rural areas. He opened a rehab center for de-addiction, where the emphasis was on treating addiction with a return to traditional Sikhism. He has also spoken about the other problems afflicting Punjab: youth unemployment and mass migration out of India.

The tide began to turn against Amritpal when reports of violence and threats began coming in.

In November 2022, he began a “caravan”, or a convoy, between villages in Punjab, surrounded by supporters, who were seen carrying automatic weapons and advocating secession. In December 2022, Amritpal supporters committed arson, dragging chairs and benches out of Sikh temples, where they are often installed for the elderly who find floor sitting difficult, and destroyed them. They were trying to enforce the edict that anything but floor-seating in a place of worship is sacrilegious.

These stringent rules were rejected in other quarters of the Sikh community. In a Punjabi-language video seen on X, an elderly woman in a temple, sitting on a bench, rails against the arson and the attempt to define what is proper Sikhism for everyone. “Respect for mothers should be paramount,” she says.

In a video hosted by the Sikhi-Vichaar forum, scholar Karmindar Singh Dhillon explained that the rules barring raised seating are about preventing discrimination. Permitting the elderly and disabled to participate in ceremonies is not discriminatory, he said, therefore not sacrilege.

Then, a former supporter of Amritpal alleged that he had been kidnapped and beaten by the Amritpal group, leading to the arrest of one of Amritpal’s supporters.

The situation escalated when, on Feb. 23, 2023, accompanied by hundreds of supporters, Amritpal stormed the police station where their associate was being held, forcing the police to release him. Six policemen were injured during the attack, which occurred in the town of Ajnala.

The next month, police began a “mega crackdown” on Amritpal’s supporters and group, Waris Punjab De, with 78 arrests on the first day, although Amritpal remained at large. A manhunt ensued over the next 37 days. Police sealed Amritpal’s village. In order to quell protests that were springing up, they turned off the internet for 27 million people for more than 24 hours. Eventually Amritpal was arrested and detained under the National Security Act, under which people can be held for a year as a preventative measure.

Amid the haul captured by police, they found insignia of a militia that they alleged Amritpal was trying to raise, the Anandpur Khalsa Force. Some of the logos were in the form of holograms, some were on bulletproof vests. They also found AK47 automatic weapons, weapons-training videos, and ten dollar bills of an imagined Khalistan currency. Police also alleged that men who were treated for de-addiction were later “indoctrinated and given martial and weapon training.”

The last allegation was investigated by newsmagazines India Today and The Print. They interviewed some former inmates of the rehab center who claimed to have been treated using inadequate pills, such as painkillers, without the aid of a medical doctor. Some attested to being beaten and tortured if they tried to leave. The rehab center personnel, in the interview with The Print, denied that the inmates were given weapons training.

The arrest cut short Amritpal’s meteoric rise as a modern-day avatar of Bhindranwale. At the same time, “Free Amritpal Singh” has become a rallying cry among the Sikh diaspora. Protests about freeing him have been held in several US cities, including San Francisco, New York, and Chicago. He has become a symbol of the “Bandi Singhs”, the Sikh prisoners that are held in Indian prisons pending trial in the government’s draconian crackdown on separatist politics.

Amritpal himself is now a “Bandi Singh”, since he has been detained for more than a year.

His candidacy has gained a devoted following in some parts of his constituency. Khadoor Sahib is a rural, devout region where the intertwining of politics with issues of Sikhism have held purchase over the years. He is being represented by his mother Balwinder Kaur, and his father Tarsem Singh on the campaign trail. A motorcycle rally traveling around the region features his mother sitting on the roof of a car, greeting voters, and his father riding pillion on a motorbike.

Two Facebook pages have run ads for the Amritpal candidacy: a page with an English name, “We Support Bhai Amritpal Singh 2024” and one with a Punjabi name, “Sada MP Bhai Amritpal Singh 2024”. Across both pages, they have run over 200 Facebook ads since May 21. Both pages feature identical content. Voters are being asked to support Amritpal as a proxy for the wellbeing of the Sikh community: in a video, his father made an explicit appeal for electing his son as a representative of Sikhism, versus the rivals who represent politics.

Some posts highlight the searing memory of 1984’s pogrom on Sikhs, and place his candidacy directly in opposition to the government in New Delhi. These pages and posts on the campaign Instagram account graphically instruct voters on how they must vote: press 12 alongside Amritpal’s election symbol, which is a microphone, on the electronic voting machine.

According to a report by The Print, issues from Amritpal’s 10-point manifesto that draw voters’ interest are issues that affect the local population, such as the scourge of drug addiction, soil and water pollution, justice for Bandi Singhs, and so on. Separatist politics and “Khalistan” do not surface.

However, Amritpal’s “pro-freedom” cause—a phrase that codes for the formation of a Sikh state of Khalistan and separation from India—is straightforwardly celebrated abroad, among the Sikh diaspora living under the protection of western free speech laws, unlike in India, where talk of Khalistan is contraband. A “Mission Khadoor Sahib” X account that appears to be run from Canada has been using the hashtag “EyesOnAzaadi”—in other words, “eyes on freedom,” in posts about Amritpal’s candidacy: a direct line being drawn from Amritpal to the struggle to separate Punjab from India.

When Amritpal was arrested last year, forty American Sikh organizations released a joint statement condemning the Punjab police’s arbitrary arrests during the manhunt. A new documentary by Canadian-Sikh photojournalist Gurkeerat Singh called “Anandpur Vaapsi”, documenting Amritpal’s caravan, has gotten over 2 million views on YouTube, and is banned in India. His candidacy was welcomed in a statement by the CSYA.

If Amritpal wins on June 4, it will be considered an earthquake on both sides. For India, the worries of Sikh diaspora-driven resurgence of radical Sikh separatism in Punjab will skyrocket. Given that these connections are formed over social media, the government has sometimes taken radical steps to censor the internet. Amritpal’s own X account “@sandhuamrit10” was suspended, as were the social media accounts of his associates and other Sikh activists.

Probably the most remarkable fact of his rise are his unlikely beginnings. Unlike Bhindranwale, who was a cleric before he rose to prominence, “Bhindranwale 2.0” (Amritpal) worked as a dispatcher in his family’s transportation business in Dubai. In that phase, he did not sport a turban or an uncut beard, and wore westernized clothing.

Like many others during the Covid-19 pandemic, he got involved in politics through social media. Clubhouse, the app that CNN once called the “pandemic’s hottest new app,” became an important facilitator of global conversations. The conversations were unmoderated, and yet public—a lethal combination. The app quickly became notorious for a “bro” mindset, unfriendly to wokeism and feminism, replete with GamerGate-style toxicity, before it shut down.

Amritpal was no exception. His Clubhouse chats are now lost to the ether, but his old twitter account survives on the internet archive. In the days before Deep Sidhu’s death, he is often seen to be railing against woke liberals, and sparring with Punjabi feminists. Of Sikh liberals, he insists that they must speak about Sikh justice issues before picking up unrelated ones like BLM, Palestine, and Muslim causes.

“Punjabi feminists are trying hard to play the victim card but in reality they are pathological liars,” he says in another thread relating to a dispute with a woman who said she received rape threats when she was, according to him, “ranting against Khalistan.”

Amandeep Singh, who was in those conversations, thinks the characterization of Amritpal as a Clubhouse “bro” is unfair. The critique of white liberal feminism Amritpal was making, he said, did not come from a reactionary conservative mindset, but rather, from a radical decolonial left perspective. “Why is it that violence against Palestinians or Kashmiris or Black Americans has social currency and automatic sympathy, and why is a genocide of the Sikhs not even worth a mention?” This was the issue Amritpal was debating on Clubhouse, Singh said.

Amritpal’s importance, Singh said, was that he “gave a western vocabulary to Sikh critiques that are indigenous.”

“The goal was to use western vocabulary, and western critiques of western imperialism, to give some legitimacy to our struggle. Because there's a currency attached to the English language and the western vocabulary.”

This gets to the heart of the strangeness of Amritpal’s candidacy: he is simultaneously a child of rural Punjab and of the westernized Sikh diaspora. The diaspora tends to be much more radical in their support of Khalistan than Sikhs in India, where they mostly steer clear of the issue. Amritpal has brought that diaspora mindset into an election in rural Punjab.

So radical, in fact, that many in the diaspora do not consider the Indian state legitimate, and believe that Amritpal is granting it legitimacy by even contesting in the elections. They fear that he is being coopted as we speak. Amritpal himself had opined on this topic back in his Clubhouse days.

“I don’t have much faith in the systems created by Hindustan,” he said in a chat, using the word for India that critics often use to denote that India has become a nation for Hindus only. “But to leave these seats empty is not a solution. The concept of guerilla warfare teaches that you use the government’s resources—for your own benefit.”