Who is Arsh Dalla? Canada's Perp, India's Most Wanted

How Dalla, who now heads the Khalistan Tiger Force, uses sacrilege to kickstart an insurgency in Punjab

Last October, two men visited a hospital in the town of Guelph outside Toronto. One of them had suffered a gunshot wound. The hospital treated him, but saw enough to alarm them that they called the police. The Halton Regional Police booked both for “Discharging Firearm with Intent.”

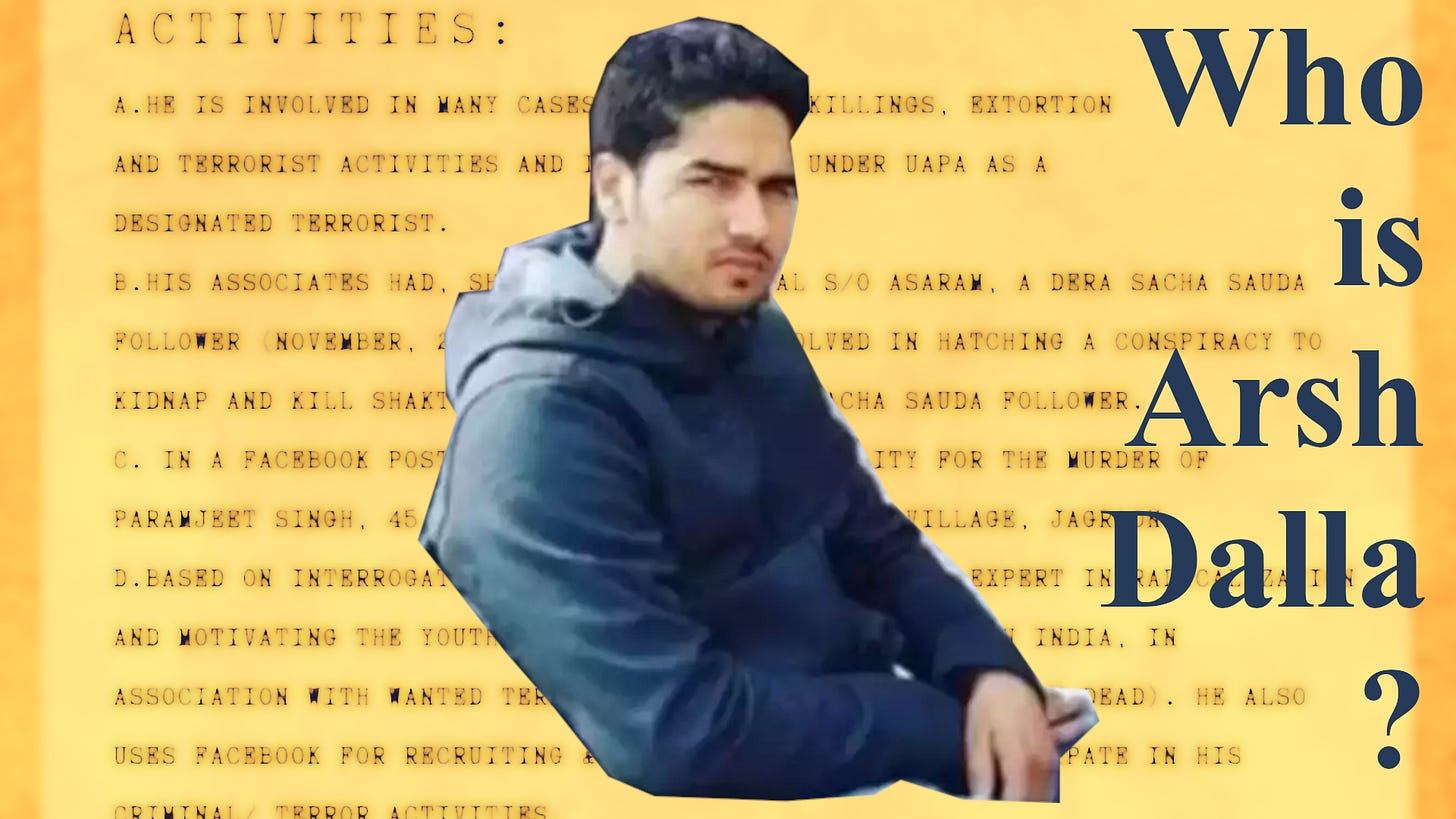

Two weeks later, the news of this relatively minor arrest made headlines halfway around the world in India. One of them was on India’s Most Wanted list. His name was Arshdeep Singh Gill, also known as Arsh Dalla.

Most Canadians were unaware that regional police had landed a high-value fugitive. But Indian media was abuzz, alerted to his identity through a leaked file.

Dalla has been on Indian front pages for years as the shadowy planner of murders across the border state of Punjab. Just ten days prior to his arrest in Canada, Punjab police announced they had uncovered Dalla’s role in the recent murder of a Sikh radical.

“Investigations have revealed that the murder [..] was masterminded from abroad by Arsh Dalla and other persons,” the head of Punjab police said, pinning only the latest in dozens of charges on him.

As news of Dalla’s arrest spread, the Ministry of External Affairs released a statement on Nov. 14 revealing that India had sought his arrest for over two years, including through an Interpol Red Notice. He had been implicated over 50 cases.

This was not a mere criminal. His activities veered into politics. He was the “de facto chief” of Khalistan Tiger Force (KTF), the statement charged, naming a militant group working to create a new nation for Sikhs called Khalistan by secession from India.

Now that Canadian authorities had him in custody, the statement said, the Indian government would be seeking his extradition. However, given Canada’s track record on such requests from India, this may turn out to be easier said than done.

Much of what follows is based on allegations in chargesheets published by Indian governmental sources.

Dalla’s bio

Dalla was a small-town gangster in Punjab when he fled to Canada in 2018. Out of reach of Indian authorities, his crime spree intensified. He began financing and orchestrating crimes back home: using drones to transport weapons, contracting with local hitmen, and smuggling in drugs.

He was alleged to be responsible for at least eight murders across Punjab since 2020. In a couple cases Dalla felt invincible enough to announce his own role through social media.

Surrey, British Columbia, where Dalla eventually settled, is the center of the Khalistan movement in the Sikh diaspora. Here, media reports say, he met Hardeep Singh Nijjar, the late Canada organizer of the separatist group Sikhs For Justice. Nijjar was then the leader of the KTF. Dalla, the Indian investigators claimed, became a KTF operative.

His crimes, that had ranged from extortion to revenge killings, now became tinged with a sectarian flavor. Dalla tried to “disrupt communal harmony,” investigators said, in chargesheet after chargesheet, by targeting leaders of rival sects and religions for murder.

Sacrilege and blasphemy

People familiar with the history of the Khalistan insurgency from the 1980s in India will have felt their nerves tingling. That near civil war, as some have called it, began as a conflict over religion.

Orthodox Sikhs had long denounced a breakway sect of Sikhism known as the Nirankaris, considering them blasphemous. In 1978, the conflict between this sect and the orthodox Sikhs of Amritsar blew up, leaving sixteen of the skirmishers dead. Two years later, the leader of the sect, Gurbachan Singh, who the orthodox Sikhs saw as the main blasphemer, was assassinated.

The conflict between Sikhs of Amritsar and the Nirankaris became a conflagration that engulfed the state. A charismatic cleric named Bhindranwale emerged as the leader of the Sikhs. Under him, the conflict that had begun as an orthodox purge of blasphemy became a full-blown insurgency. By 1984, he had fortified himself in a holy shrine, surrounded by militiamen and AK47s, ordering assassinations of the unfaithful.

Most accounts of the decade elide over the fact that that insurgency began with sacrilege, choosing to shorthand it as the Punjab or the Khalistan insurgency. However, Bhindranwale himself did not start with a demand for Khalistan.

But after he was killed by the Indian army during Operation Bluestar, the insurgency became a separatist movement out of Sikh anger at the Indian state. Cries for Khalistan rang out. Ten years of draconian action by Punjab police later, militants were decimated: some arrested, some shot dead by police, others escaping to Canada and elsewhere. Eventually, the insurgency in Punjab died out.

Given this history, if a malignant force wanted to kickstart a new insurgency in Punjab, they would be well advised to pick at the faultline between orthodoxy and sacrilege.

That, according to Indian law enforcement, was KTF’s game plan.

Gurmeet Ram Rahim

A new age, and a new blasphemer.

Since the 2010s, a religious leader with cult overtones emerged to irritate orthodox Sikhs. This man, Gurmeet Ram Rahim, leads a sect of millions of followers that once sprang from the Sikh tradition. An eccentric, narcisstic persona, he likes to dress in finery and make Bollywood-style musicals featuring himself. He has been convicted for rape and other crimes.

He became a reviled figure for Sikhs when he dressed himself in finery imitating the tenth guru of the Sikhs, thereby challenging the sacredness of one of the founders of the faith.

A low-level conflict between this sect, known as the Dera Sacha Sauda or DSS, and orthodox Sikhs, raged in Punjab ever since that act—with desecrations and religious edicts lobbed back and forth.

Some followers of the DSS sect took to performing acts that Sikhs considered sacrilegous. Pages of a Sikh holy text, ripped out of a stolen relic, were found scattered on the streets of several towns in Pubjab. The desecration controversy, that spanned from 2015 to 2021, continues to roil Punjab, with protests, resignations of leaders, and arrests. In 2015, sacrilege against the Sikh faith became a crime, punishable with a life sentence.

KTF did not create the controversy, but they jumped into it with both feet, exacerbating the low-range war between the two sects with targeted killings.

Sacrilege and a sock puppet

Around late 2020, a murder spree began in Punjab. The targets seemed to be chosen based on their faith.

One Friday evening in Nov. 2020, two young men, dressed entirely in black, with scarves covering their faces, rode up on on a motorcycle and entered an office. CCTV footage showed them shooting the man behind the counter at point blank range and fleeing. The victim, a foreign exchange trader named Manohar Lal, was a prominent DSS member whose son was one of the main accused in the desecretion controversy.

DSS followers took to the streets in protest, refusing to cremate the remains until the guilty were punished.

This was not the only attack: a readymade clothing store owner was killed in broad daylight in July 2020. A Hindu priest and a temple worker were shot at in Jan. 2021. .

While police sought the perpetrators, a local gangster named Sukha Lamme posted on Facebook claiming responsibility for the spree of murders. Breathless headlines covered Sukha Lamme’s statement, but police were tight-lipped.

The real culprits were caught in May 2021. Sukha Lamme, it turned out, had nothing to do with the murders. His posts had been a blind. In fact, he had been dead for months, his body somewhere at the bottom of a canal.

Police alleged that the three young men in custody were hired guns and the murders had been orchestrated from abroad by KTF, under the leadership of Nijjar and Dalla. Given that the murders weren’t just one-off but parts of a conspiracy, India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) took over from state police.

“Hardeep Singh Nijjar, self-styled chief of KTF…along with his associate Arshdeep Singh…recruited gangsters to effect target killings […] to disturb communal harmony in the state of Punjab,” said a chargesheet from the NIA dated Dec. 2021.

The details of what happened to Sukha Lamme were gruesome. Acording to the allegation by the head of Punjab police, Dalla had returned to India in mid-2020, and with his associates, killed Sukha Lamme at an abandoned house by injecting him with poison, burned his face, and tossed his body overboard from a bridge. Then, he sock-puppeted the dead gangster’s Facebook account and “admitted” to crimes that Dalla himself had committed.

The short arm of the law

Starting in 2014, Indian authorities repeatedly tried to have Nijjar extradited from Canada. The dossier they handed over to Canadian authorites included allegations about attacks planned on DSS followers and other figures seen by radical Sikhs as enemies of their faith. In 2018, a list of nine accused, which included Nijjar’s name, was handed directly to Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau.

However, Canadian police did not comply, questioning the evidentiary standards and human rights practices of Indian police. Other bodies, including the US State Department and Amnesty International, have agreed with this assessment.

Nevertheless, the Indian government was left with what seemed to be an active campaign of violence in Punjab by KTF operatives, including Nijjar, Dalla, and others, and what they saw as a recalcitrant foreign government harboring the accused as untouchable. They declared KTF a terrorist outfit in early 2023.

In June 2023 Nijjar was shot dead while at the wheel of his truck as he exited a parking lot. Trudeau accused the Indian government of having orchestrated the murder. Some Canadian investigators believed that India killed Nijjar because they could not get him extradited though legal means. But in a reversal of roles, this time it was the Indians questioning the Canadians’ standard of evidence.

As both sides have been tight-lipped about the substantiating details that led each to make their allegations, short of a trial, the truth of the matter remains unresolved.

However, Nijjar was well known to be associated with the KTF among Sikh activist circles.

At the start of 2023, Dalla hit a milestone: he became a declared terrorist according to India’s Ministry of Home Affairs. They listed murder, extortion, targeted killings, terror financing, and cross border smuggling of drugs and weapons as his crimes.

KTF under Dalla

After Nijjar’s death in 2023, Indian investigators alleged that Dalla took over the leadership of KTF.

The year 2023 saw another rash of brazen killings that police attributed to Dalla and KTF. With the widespread prevelance of surveillance cameras, footage was captured from a few of them. They showed a similar pattern. The assailants were usually two men on a moterbike with their faces covered with scarves. The deed was done in a matter of seconds, after which the attackers fled on the motorbikes. Sometimes, they were caught on camera as they were fleeing.

In September, a political leader from the Congress party was lured to the gates of his home and shot dead. Dalla claimed on Facebook that he had ordered the hit as vengeance.

In October, the owner of a snack shop was shot in broad daylight as he sat outside his shop checking his phone. Punjab police alleged Dalla’s involvement in that murder as well.

Indian authorities made multiple attempts to have him arrested in Canada, once in July 2023 and then again in March 2024, to no avail.

Late last year in October, the conflict turned inward, taking the life of one of their own. A radical Sikh activist, prominent among the small, tight group of Khalistan advocates in Punjab was shot at as he rode home on his motorbike in the evening of Oct. 9.

This activist, Gurpreet Singh Harinau, was one of the activists to emerge from the 2020-21 farmer protests in Punjab. On the fringes, the farmer protests became entangled with radical Sikh politics and gave rise to a new political party, Waris Punjab De, where Harinau was a founder member. He had a popular following on Facebook and YouTube.

In the last few months, a factional battle had arisen among the leadership of the party and Harinau had gotten death threats from the opposing faction. The dead man’s family went to the police with their suspicions, pointing the finger at jailed Member of Parliament, the preacher Amritpal Singh. The MP’s men, they said, had been issuing increasingly angry threats to the dead man in the few weeks before the shooting.

Ten days afer the murder, Punjab police claimed to crack the case and made official allegations.

During their Oct. 17 press conference, the chief of police said their investigations had led them, once again, to Dalla, and accused him of directing the conspiracy from Canada. They also noted that they had received tips about the MP, Amritpal Singh’s involvement.

Surprisingly, Dalla himself decided to provide commentary on the police announcement. They were wrong, he asserted. Amritpal Singh had nothing to do with the killing—it was all him.

The caller purporting to be Dalla called a local news channel the day of the police announcement. He, himself, he said, had gotten Harinau killed—in order to punish him for objectionable pictures he had posted on social media.

Dalla’s four-minute-long message showed how, just like in the 1980s, militant separatism in Punjab continues to be entwined with vigilante zealotry. He railed against vulgar Instagram posts by Sikh women. He exhorted others to kill all who had committed sacrilege against the Sikh faith.

“Those who disrespect our community will get what they deserve,” he said.

“Long live Arsh Dalla,” said a comment on the video.